DETAILED LEGIONELLA FACT SHEET

Legionellosis is a lung infection – an uncommon form of pneumonia – caused by a bacterium named Legionella pneumophila. There are two forms of legionellosis: Pontiac Fever, the less severe form, and Legionnaires’ disease, the more severe illness that is potentially fatal. Legionnaires’ disease was named after the original outbreak of the disease at the 1976 American Legion Convention in Philadelphia - Legionella to honour the American Legionnaires that were infected, and pneumophila from the Greek word meaning ‘lung-loving.’

Legionella is found everywhere in the environment. It is a natural inhabitant of water and is found at the air-water interface in surface water (rivers, lakes and streams) and in aerated biofilms. Interacting with other microorganisms found in the environment may help Legionella grow and survive. Legionella can survive in sterile tap water, and survive and multiply in non-sterile sources.

Legionella can infect and enter different protozoan hosts. It replicates quickly inside a host cell so that one host cell may contain hundreds of Legionella cells. When Legionella is inside a protozoan host cell it can survive a wide range of environmental conditions and resist being killed by chlorine, biocides (chemical agents capable of destroying living organisms) and other disinfectants. Relationships with biofilms also help Legionella grow because the biofilms provide Legionella with nutrients and protect it from being killed when a water source is disinfected.

In one month, Legionella may multiply from less than 10 cells per millilitre to over 1000 cells per millilitre of water if under the proper growth conditions. Legionella grows well in warm, motionless waters. Water conditions like this are found in cooling towers, evaporative condensers, humidifiers, air washers, mist machines, hot water heaters, whirlpool spas, fountains, hot springs and plumbing fixtures. The bacterium has been found in water with temperatures ranging from 6°C - 60°C (42.8°F-140°F). It will not multiply below 20°C (68°F) and dies above 60°C (140°F). Legionella bacteria at 37°C (98.6°F) are more infectious than the same bacteria at 25°C (77°F), meaning that warm water between 20°C (68°F) and 45°C (113°F) is the perfect place for the bacteria to multiply. Other places that Legionella can multiply include: hot and cold water tanks, pipes with little or no water flow, slime (biofilms) and dirt on pipe and tank surfaces, rubber and natural fibres in washers and seals, water heaters, hot water storage tanks and residue/build-up in pipes, showers and taps. The major sources of Legionella are the water distribution systems of large buildings including hotels and hospitals.

Legionella has qualities that make it different from other bacteria cells. It needs to be in areas with low levels of oxygen to survive and can live in waters with a range of acidity levels.

Diagram of bacterium

How do I Get the Disease?

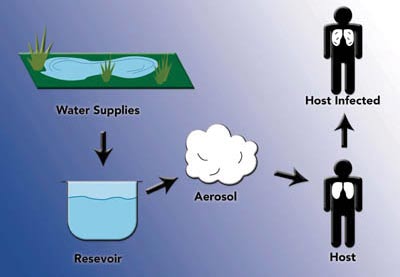

Inhaling small aerosol particles that contain Legionella is the most popular theory of how people get infected with legionellosis. Outbreaks of legionellosis have occurred when people breathed in mists from a water source contaminated with Legionella. These sources include: air conditioning cooling towers, whirlpool spas and showers. People may be exposed to these mists in homes, workplaces, hospitals, or public places. There is no evidence of people getting infected from auto air conditioners or household window air-conditioning units.

New evidence shows that there is a more common way of contracting the disease. One way is ‘aspiration.’ Normally, secretions from the mouth go through the esophagus into the stomach. When choking, the secretions get past the choking reflexes and enter the lungs by mistake. This is known as aspiration. This is the common way bacteria enter the lungs to cause pneumonia. Direct infection of surgical wounds through contact with contaminated tap water has also been described.

Legionella is transmitted directly from the environment to humans. To cause an infection, the Legionella bacterium must escape the host defences of the human body. It enters the lungs when foreign particles, including bacteria, fall directly into the respiratory tract (trachea (‘windpipe’) and lungs). The aspiration infection cycle – the under-recognized infection process – is described below.

The bacterium enters the mouth, perhaps by drinking contaminated water, and cannot usually enter the lungs due to the presence of cilia on the cells of the respiratory tract. Cilia are microscopic hair-like processes that are capable of rhythmic motion and act in unison with other structures to bring about movement of the cells or of the surrounding medium. However, in sick patients or in patients that smoke, the ciliary process is impaired making it easier for the Legionella bacteria to bypass the gag reflex and enter the respiratory tract. Legionella can also stick onto the cells of the respiratory tract, enter them and multiply once inside.

When Legionella has entered the lungs, the immune system will signal neutrophils and macrophages (two types of white blood cells) to the infection site and they will try to swallow up the bacteria to kill them. The alveolar macrophages are the most important cells in the infection process. Once Legionella is swallowed up, it can escape the killing mechanisms of the immune system and start multiplying inside the cell. Legionella is referred to as an intracellular pathogen because of this quality.

Legionella will continue to multiply inside the macrophage until there is no longer room for new bacteria to grow. The large amount of bacteria inside the macrophage will cause it to burst and the bacteria will then be released into the lungs. The newly-released bacteria will be engulfed by other macrophages and the cycle will continue. The immune system will recruit other types of white blood cells to kill the invading bacteria, but Legionella can escape being killed by hiding in the cells of the respiratory tract or in the alveolar macrophages. The combination of white blood cells and bacterial enzymes will produce the damaging alveolar inflammation associated with the pneumonia caused by the bacteria.

Outbreaks

Every year in the United States there are 8000 – 18000 reported cases of legionellosis. In 2015, there were 328 reported cases of Legionellosis across Canada in people of all ages.

Outbreaks of legionellosis receive much media attention, although this disease usually occurs as a single, isolated case not associated with any recognized outbreak. When outbreaks do occur, they are recognized in the summer and early fall, but may occur year-round.

Cases of legionellosis have been reported in North and South America, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and Africa. Legionellosis outbreaks have most frequently been credited to contaminated drinking water, cooling towers, or components of water distribution systems. Travelers can be exposed to Legionella in contaminated hotel drinking water or contaminated whirlpool spas. Outbreaks in hospitals have been linked to hospital drinking water supplies, air conditioning systems and cooling towers, while community outbreaks are often caused by exposure to a wide variety of sources, with drinking water and cooling towers again being the most common.

What Are the Symptoms and the Incubation Time?

The symptoms of this disease are not any different from the symptoms associated with other types of pneumonia, although, Legionella causes a severe type of pneumonia that requires immediate medical attention.

The incubation period (time from bacteria exposure to the appearance of the first symptoms) for Legionnaires’ disease is 2-10 days, with an average onset of 3-6 days. Those that are infected may feel tired and weak for several days. Early symptoms of the disease include: fever, chills, body aches, headache, loss of appetite, and gastrointestinal illness (i.e. diarrhea) that occurs in 20-40% of cases. A cough, either dry or sputum (matter coughed up from the respiratory tract)-producing, may also develop. Later symptoms of Legionnaires’ disease include chest pain, dyspnea (difficulty breathing) and respiratory distress. Those who are admitted to the hospital often develop a high fever greater than 39.5°C (103°F). For patients that are discharged from the hospital, many will experience fatigue, loss of energy, and difficulty concentrating for several months.

The incubation time for Pontiac fever is much shorter, taking only a few hours to 2 days (generally 24-48 hours) to produce illness. Pontiac fever is a self-limiting disease with rapid onset and a short but severe course of illness. It causes flu-like symptoms that include fever, chills, headache, myalgia (muscle pain or tenderness), and malaise. Pneumonia does not develop in this case.

How Long do the Symptoms Last?

Those with Pontiac fever will generally see their illness resolve without complication within 2 to 5 days. Those who develop Legionnaires’ disease will have varying recovery times dependant on the severity of the symptoms developed.

How is it Diagnosed?

Since the symptoms of pneumonia caused by Legionella are not any different from those caused by other types of pneumonia, laboratory tests must be carried out to determine whether or not the illness is caused by Legionella. To diagnose legionellosis, specialized laboratory tests are required. There are many different tests and each has positive and negative properties. Some of these tests are: culture on specialized Legionella media; direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) in which the bacterium can be stained and becomes visible under a fluorescent microscope; antibody testing – a blood test in which antibodies that are reactive against Legionella are present in the human body showing that the patient has previously come into contact with the bacterium and urinary antigen – a test that detects Legionella in urine. The preferred diagnostic method is culturing because it is sensitive and specific, although a common setback is that appropriate test specimens are not always available.

The following table gives a summary of each testing method.

Table 1: Laboratory methods for clinical diagnosis of Legionella infection

Who is at Risk?

The general population is fairly resistant to infection. However, certain groups, such as middle aged and elderly people, are at a higher risk… especially those who are smokers and those with chronic lung disease. Males are also at a greater risk than females. Another group of people who are at increased risk are those who are immunocompromised including people with immune systems repressed by certain medications or by certain diseases, such as cancer, kidney failure during dialysis, AIDS and diabetes. Organ transplant patients are at most intense risk because the medicines used to protect the new organ also compromise the patients’ defence system against infection. This disease is rare among children, although newborn infants less than four weeks old may be at increased risk of contracting Legionella infection because their immune systems are underdeveloped.

Pontiac fever most commonly occurs in people who are otherwise healthy.

Am I at Severe Risk for Disease?

If legionellosis is treated with antibiotics near the onset of pneumonia and if you are in good health and do not have any underlying illnesses that may compromise your immune system, the outcome of illness will be excellent. For immunocompromised patients, including transplant recipients, any delay in appropriate treatment may result in prolonged hospitalization, severe complications and death. For patients that are discharged from the hospital, serious consequences are not common. Fatigue and weakness are two chronic conditions that may persist for several months following treatment, although complete recovery usually occurs in about one year.

There are two very different kinds of respiratory illness that may result from infection with Legionella. The most common is acute pneumonia that varies in severity from mild illness not requiring hospitalization to multi-lobe pneumonia that is fatal. Sometimes, Legionnaires’ disease will cause mild respiratory abnormalities with serious abnormalities being rare. Pulmonary fibrosis, defined as the formation of excess fibrous tissue in the lungs and chronic vasculitis, defined as long term inflammation of blood vessels, are lung-associated diseases that have been reported.

Although it rarely occurs, Legionella has been known to infect areas outside of the lungs. The heart and kidney are the most common sites for this type of infection. Bacteraemia, a bacterial blood infection, may also occur from a Legionella infection.

How Can I Prevent Getting Legionellosis?

You cannot become infected with legionellosis by drinking contaminated water that will enter your stomach in a normal way; the bacteria have to be breathed in so to gain access to your lungs. The most common risk factor is smoking because it damages the cilia on the cells that line the throat thereby making it easier for Legionella to bypass this defence mechanism. To decrease the chances of getting infected with Legionella, you should stop smoking.

One approach to preventing Legionnaires’ disease is to find the Legionella source in the environment and then proceed to get rid of it. Reducing the risk means breaking the chain of transmission between environmental sources of Legionella and potential human hosts. Regular inspections of hot water systems should be done. Being on the look-out for Legionella infections, especially among hospital patients that are considered ‘high risk’, is also an important tool for reducing illness because it allows for immediate corrective action, rapid diagnosis and treatment of confirmed cases.

How do I Prevent Spreading it to Others?

Legionella is transmitted directly from the environment to humans. There is no evidence of it being spread from human to human or from animal to human.

What is the Treatment for Legionellosis?

Early detection and early treatment are essential for a successful outcome to Legionnaires’ disease. This is important because between 5-30% of cases are fatal. Pontiac fever does not require any specific treatment.

Legionella is an intracellular pathogen and this fact is important when deciding what medications to use. Many antibiotics that are usually effective against pneumonia are ineffective against Legionella because they (the antibiotics) do not enter the respiratory tract cells or alveolar macrophages. Antibiotics designed specifically for Legionella pneumonia must be used. Treatment consists of intravenous administration of the antibiotics that continues until fever subsides. At this point, intravenous treatment can be replaced by oral therapy.

Erythromycin has usually been considered the antibiotic of choice for the treatment of Legionnaires’ disease, but newer antibiotics that are more potent and less toxic are now replacing it. Newer antibiotics called macrolides (ex. azithromycin) have shown greater success in eliminating Legionella, and also cause fewer side effects. Quinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin, trovofloxacin) have also shown greater activity against Legionella species, with an even higher success rate than the macrolides. These antibiotics (quinolones) have been recommended for transplant recipients with Legionnaires’ disease because, unlike macrolides, they do not interfere with immunosuppressive medications. Other agents also shown to be effective include tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, and trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole.

How Prevalent is Legionella in Surface Water/Well Water?

Legionella is a natural inhabitant of water, including both natural and man-made sources, and can be found at the air-water interface in surface water (rivers, lakes and streams). Research has made known that the presence of biofilms and other organisms in water is important for the survival and multiplication of Legionella. Because bacteria in biofilms are quite resistant to standard water disinfection procedures, Legionella is able to enter and live in drinking water supplies. The water supply will also help Legionella multiply and spread.

Groundwater is also at risk of being infected with Legionella and hot springs have also shown to be a natural source of the bacteria.

Is My Water Safe? How can I Tell?

Testing for Legionella is a useful tool and is the only way to determine if the bacterium is present in your water supply. It is strongly recommended that trained employees carry out all testing procedures to avoid the possibility of false positives, or inconsistent, unreliable results. Laboratories that are qualified to test water for the bacteria should examine the water samples.

What Are Some Ways I Can Treat My Water to Ensure its Safety?

The basis of preventing the growth of Legionella is to improve the design and the maintenance of cooling towers and plumbing systems, thus limiting the spread of the bacteria. Until newer and improved designs are put into practice, there are a variety of ways to treat the water supplies to lessen the spread of the bacterium.

There are several control methods available for disinfecting water distribution systems. These methods include thermal disinfection (super heat and flush), hyperchlorination, copper-silver ionization, ultraviolet light sterilization, ozonation, and instantaneous stream heating systems. Each method has positive and negative qualities and has proven effective to various degrees. Some treatments are not completely successful in removing the all of the bacteria while others do not provide permanent protection against its re-growth. A combination of various methods may be the most effective way of protecting the water supplies. A description of each water treatment method, based on information from the USEPA “Legionella: Drinking Water Health Advisory” document is given in the table below.

There are two defined categories of disinfection, focal and systemic. Focal disinfection is directed at a specific portion of the system and would include: ultraviolet light sterilization, instantaneous heating systems, and ozonation. Systemic methods, such as thermal disinfection, hyperchlorination and copper-silver ionization, disinfect the entire system.

Did you know that our Operation Water Health program is available free of charge to teachers worldwide and provides the teachers with all of the lesson plans and information they need to teach students about what safe drinking water is, what unsafe drinking water is, and what health problems can be caused by unsafe drinking water? Please help us to keep our Operation Water Health program up-to-date! Please chip in $5 or donate $20 or more and receive an Official Donation Receipt for Income Tax Purposes.