THE CREE LANGUAGE FACT SHEET

Are there a Lot of Cree Speakers in Canada?

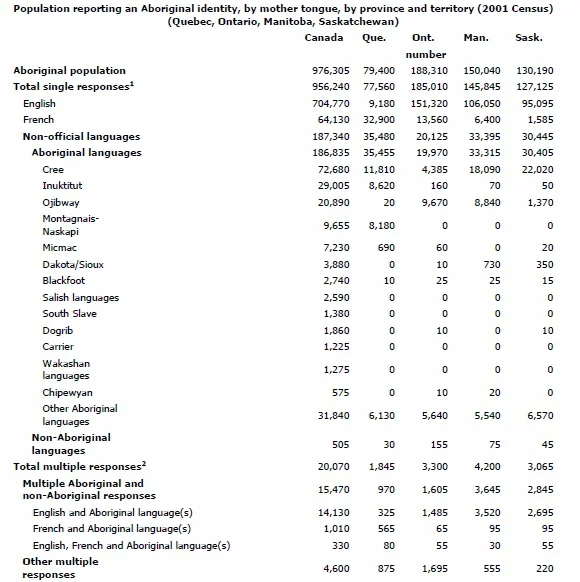

The Cree language is spoken by approximately 75,000 people across Canada, making it the most spoken of Canada’s Aboriginal languages. More than 75 percent of the Cree speakers live in Alberta, Saskatchewan or Manitoba. The table below shows the distribution of languages that are spoken by Aboriginals in Canada.

Population Reporting an Aboriginal Identity, by Mother Tongue, By Province and Territory; Statistics Canada

How Many Dialects are There?

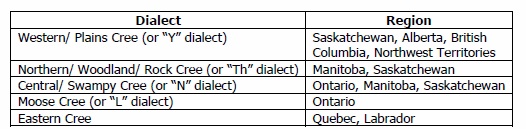

Dialects are varieties of a language that differ in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar (but it is not the same as an accent). You may have known that Canadians spell some words differently than Americans (for example, colour and color; organisation and organization), but you may be surprised to know that there are a number of dialects of the English language. People speaking different dialects of a language are usually able to communicate with each other because the dialects are similar enough that they can understand each other. Cree is an Algonquian language with several dialects. The chart below summarizes the five major Cree dialects, including the regions of Canada in which they are spoken.

This map shows the rough boundaries of the regions in which each dialect is spoken. It is difficult to accurately classify the dialects and regions, because there are so many dialects, some of which are widely spoken, like Plains Cree, and others that are not common, such as Moose Cree.

Primary Cree Dialects and Canadian Regions in Which They are Spoken

Distribution of Cree Dialects in Canada;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cree_language

How Did the Written Cree Language Develop?

One theory of the word Cree is that it originated from the Ojibway word kristanowak , and the Jesuit word kristinue , which both mean “people of the north.” This was eventually shortened to kris (Crees).

The other theory of the word Cree is that it originated because the Cree were the first to be Christianized and subjected to colonialism. The acronym for Cree was Christino , meaning Christianized Indian, which came to be known as Cree. The self-identifying term used by the Cree is Ininiwuk , meaning men, or the original people. The Plains Cree of Alberta and Saskatchewan, Woodland Cree of Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and Swampy Cree of Manitoba and Ontario, all belong to this family.

The Jesuits were the first to try to write the Cree language as they heard it spoken. There are oral stories which state that syllabics were given by the Creator to the people. It is the belief of many traditionalists and academics that syllabics were written prior to the use in the Jesuit Bible, yet like many Aboriginal inventions, another person or group took the claim for it.

Cree dialects can be written using Cree syllabics or the Roman alphabet. The Cree syllabary was developed when the Cree and the Jesuits taught each other their language and culture. The artistic communication of the Cree (who used drawings and symbols) combined with the literal communication of the Jesuits to develop a unique set of Cree syllabics.

When children were placed in residential schools, they were taught to read and write English. As they learned the English alphabet, the use of Cree syllabics declined. While the syllabic writing system was used in church environments, the English language prevailed in schools, stores and the government. Because children were taught the English alphabet, they soon began writing Cree using the English alphabet. The Cree syllabics are presently being resurrected within the school systems.

What are Some Places in Canada that Have Cree Names?

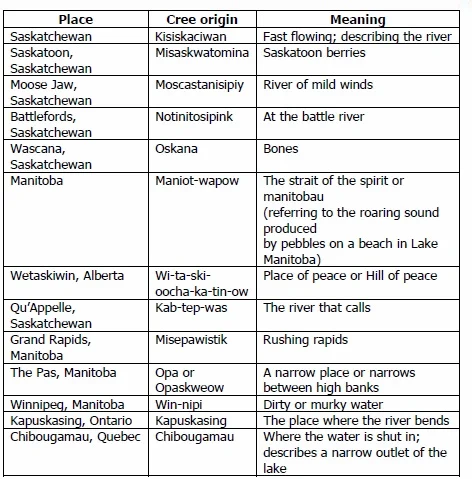

Aboriginals first named places to identify the land that they knew, and many of the cities and provinces across Canada have names that originated from these Aboriginal names. The following chart summarizes several places that have names of Cree origin and their meaning.

Canadian Locations with Cree Names;

http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/

What is the Cree Perspective of Water?

The following is an excerpt from a presentation to the Watershed Science Centre by Chief Kenny Blacksmith, Founder of Gathering Nations International and Former Deputy Grand Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees in Quebec. In a time where the idea of selling Canada’s water is being considered, Chief Kenny Blacksmith’s presentation sheds some light on the Aboriginal

perspective of water use and misuse.

“’Nipiih’ is vital to the well-being of lands and to its flora, fauna and to the integrity of our environment as a whole. In terms of our history, culture and survival, ‘nipiih’ has always been and continues to be, a critical significant life giving resource to our people, our communities and our nations. Water or ‘nipiih’ is intricately involved in all aspects of life.”

Chief Blacksmith goes on to state three principles that explain the Cree perspective on

water and guide environmental decision making:

1. “The profound relationship we continue to have with our lands, waters, resources and environment.”

2. “Our stewardship responsibility for our present and future generations.”

3. “The principle of sharing of water and all other resources.”

The next excerpt is from a letter that was written to the Federal Regulators on January 21, 2004, in regards to a possible diamond mine in the James Bay lowlands in Ontario. Mike Koostachin, an Attawapiskat First Nation member, wrote the letter to share the views of the Cree people with regards to the mine development and the surrounding environment.

“First and foremost of our concerns regarding this development is the impact on our river. Since ancient times we have regarded water as a precious element, and hold it as a sacred part of our ceremonies. The creator used this sacred element, along with that of air, the spirit of fire, and mother earth herself to create humanity. All living things are made up of water and depend on it to live. Indeed, not one of us can blink an eye, draw breath, or even speak without water. Every cell in our beings requires this element in order to function. Today, as in ages past, we still honor this life giving force in our daily ceremonies. The women of our nations are the ones who conduct the water portion of our ceremonies, since they share with water the power to bring forth life. It is the eldest and wisest women present, usually a grandmother who conducts the teaching and instructs the rest of the women about responsibility to care and protect the water as a powerful spiritual and medicinal entity. We know that our community, as well as the James Bay and the surrounding rivers are like the veins of mother earth.” (http://www.miningwatch.ca).

The words of these two Cree men offer a glimpse into the Aboriginal perspective of water and the importance of protecting our water sources. For more information about the Aboriginal perspective of water, see the Operation Water Spirit program, or the Ojibway and Inuktitut fact sheets.

The Safe Drinking Water Foundation has educational programs that can supplement the information found in this fact sheet. Operation Water Drop looks at the chemical contaminants that are found in water; it is designed for a science class. Operation Water Flow looks at how water is used, where it comes from and how much it costs; it has lessons that are designed for Social Studies, Math, Biology, Chemistry and Science classes. Operation Water Spirit presents a First Nations perspective of water and the surrounding issues; it is designed for Native Studies or Social Studies classes. Operation Water Health looks at common health issues surrounding drinking water in Canada and around the world and is designed for a Health, Science and Social Studies collaboration. Operation Water Pollution focuses on how water pollution occurs and how it is cleaned up and has been designed for a Science and Social Studies collaboration. To access more information on these and other educational activities, as well as additional fact sheets, visit the Safe Drinking Water Foundation website at www.safewater.org.

Did you know that our Operation Water Health and Operation Water Spirit educational programs are available in Cree? Also, some of our fact sheets are available in Cree! Please help us to continue to offer our educational programs in other languages! Please chip in $5 or donate $20 or more and receive an Official Donation Receipt for Income Tax Purposes.

Resources:

Presentation to the Watershed Science Centre, Environmental & Resource Science, Trent

University. April 2007. Drinking Water: The How, Why and Who of Source Protection.

https://www.trentu.ca/iws/sites/trentu.ca.iws/files/documents/SWP_Blacksmith.pdf.