ASBESTOS IN WATER AND ASBESTOS CEMENT WATER PIPES FACT SHEET

What is asbestos?

Asbestos is a general term for a variety of fibrous silicate minerals which can be separated into soft, silky fibres. These minerals are divided into two main classes on the basis of their crystal structure – the serpentine and amphibole groups. Chrysotile (white asbestos) is the only fibrous member of the serpentine group, and it is the main type of asbestos used in manufacturing.

How did asbestos come to be in pipes?

In 1906, an Italian company combined asbestos fibres with cement to produce a reinforced water pipe. The asbestos cement (AC), or transite pipe, was first introduced in North America in 1929. AC pipe was a common choice for potable water main construction during the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. According to a 1977 Health and Welfare Canada report, “More than 99.9% of the asbestos fibre produced in Canada was chrysotile.” Chrysotile comprises 80% or more of the asbestos used in asbestos cement pipe.

James Hardie and Wunderlich float advertising asbestos cement, ready for the Victory Day procession in Brisbane, Australia in 1946. Source: https://watershedsentinel.ca/articles/poison-pipes/

The use of asbestos cement pipe was largely discontinued in North America in the late 1970s due to health concerns associated with the manufacturing process of AC pipes and the possible release of asbestos fibres from deteriorated pipes. It has been estimated that up to 18% of the water distribution pipes in the United States and Canada are asbestos cement. The pipes can contain up to 20% asbestos. The life of the pipe can be 50-70 years, depending on soil type, climate and the aggressive nature of the water.

It has been determined that the pipes deteriorate, and their breakage frequency increases with age. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says asbestos fibres may be released from natural sources such as erosion of asbestos-containing ores, but the primary source is through the wear, or breakdown, of asbestos-containing materials, particularly from the wastewaters of mining and other industries, and by the use of asbestos cement pipes in water supply systems.

When was it realized that asbestos pipes are an issue?

The issue of asbestos in water first came to light in the early 1970s, when the EPA launched a legal action against the Reserve Mining Company. The landmark court case focused North America, and the world, on the issue of asbestos in water. For decades, the mining giant had been dumping iron-ore tailings into Lake Superior. During the investigation into the Reserve case, it was revealed that a litre of water in nearby Duluth, Minnesota had as many as 644 million amphibole fibres in it. At the conclusion of the trial, Reserve was ordered to stop dumping its waste into Lake Superior.

One of the major questions to answer was whether mineral fibres in drinking water accumulate in the body as inhaled fibres do? Dr. Phillip M. Cook, with the EPA, provided the first documentation that mineral fibres do pass through the gastrointestinal tract wall. During the trial, experts testified that the ingestion of asbestos was the likely explanation of an increased number of cancers. Dr. Irving Selikoff testified that he believed ingested asbestos caused cancer. “Secondly, although I stated yesterday that there are a number of routes, including hemotogeneous, whereby fibres could influence the gastrointestinal tract, in my opinion the best explanation is ingestion to explain the two, three times increase in the incidence of death of gastrointestinal cancer among occupationally exposed workers. So that in this sense, although there is no absolute proof, the kind that we would ordinarily want; there is, in my opinion, a very reasonable probability to state that this is the case.” Selikoff’s reasoning was simple; inhaled asbestos was also ingested. In the decades previous, Dr. Selikoff had been instrumental in highlighting the dangers of inhaled asbestos.

At the conclusion of the Reserve trial, it was a generally accepted fact that the issue required more study. The EPA launched a series of studies into asbestos in water, the potential danger of ingested asbestos, and the role asbestos cement water mains might play in contamination.

More study was conducted, and more organizations published reports and called for the prohibition of AC pipe in water supply systems

In February 1973, the Centre for Science in the Public Interest called for the “prohibition of AC pipe in water supply systems.” In a written submission, the group told the EPA that it believed “AC pipe contamination of drinking water from erosion and maintenance may present a major hazard to the general public.” It pointed to Dr. Selikoff’s testimony in the Reserve case that “there is ample reason to believe that ingestion of the major varieties of asbestos leads to increased risk of gastrointestinal cancer.”

In 1976, the American Academy of Pediatrics published Carcinogens in Drinking Water. It pointed to two studies conducted into the issue. “Both reports pointed out that in animal experimentation ingested fibers have not produced cancer, but there appears to be no doubt that there is an increased frequency of human gastrointestinal cancer after occupational exposures – presumably from asbestos that has been swallowed.”

One of the first studies conducted outside of the United States was by Health and Welfare Canada. Posted on the current Health Canada website under Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality: Guideline Technical Document – Asbestos, it reads: “Chrysolite was the predominant type of asbestos identified in a survey of drinking water supplies conducted at 71 locations across Canada in 1977.” The web page goes on to state: “Based on the results of this survey, which encompassed the water supplies of about 55% of the Canadian population, it was estimated that 5% of the population receives water with chrysotile concentrations higher than 10 million fibres/L and that 0.6% receives water containing more than 100 million fibres/L.” (The current allowable limit in the United States is 7 MFL).

In the 1979 report Exposure to Asbestos from Drinking Water in the United States, the EPA looked at asbestos concentrations in 365 cities in 43 states. “Of the 365 cities, 165 or 45.3% were reported to have significant concentrations of asbestos in the drinking water”.

In 1980, the EPA conducted a detailed study entitled Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Asbestos. In part it reads; “Asbestos is a known carcinogen when inhaled. The demonstrated ability of asbestos to induce malignant tumors in different animal tissues, the passage of ingested fibers through the human gastrointestinal mucosa, and the extensive human epidemiological evidence for excess peritoneal, gastrointestinal, and other extrapulmonary cancer as a result of asbestos exposure suggests that asbestos is likely to be a human carcinogen when ingested.”

In 1983, Dr. Joseph Cotruvo, the former Director of the Drinking Water Standards Division with the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), authored the Commentary: Asbestos in Drinking Water: A Status Report. In the paper, Cotruvo discussed the options facing the EPA with regard to regulating asbestos. He said one of the options facing the agency was to “establish a numerical limit, called a maximum contaminant level (MCL) expressed in terms of fiber count.”

In 1987, the United States Department of Health and Human Services released a study entitled Report on Cancer risks Associated with the Ingestion of Asbestos. The report concluded: “Sufficient direct evidence is not available for a credible quantitative cancer risk assessment of asbestos ingestion at this time.” However, a few paragraphs later it also wrote “Nonetheless, this should not be taken to mean that the potential hazard associated with ingested asbestos is an unimportant issue which does not warrant further research. Even if the increased rate of cancer is less than 10% of the background rate and cannot be demonstrated by available research tools, the ingestion of water, food, or drugs laden with asbestos by millions of people over their lifetimes could result in a substantial number of cancers.” The report goes on to say that several members of the working group felt it was “prudent public health policy to recommend eliminating possible sources of ingestion exposure to asbestos whenever and to whatever extent possible.” A few sentences later the report highlights “eliminating asbestos cement pipe in water supply systems.”

In 1974, the United States Congress had passed the Safe Drinking Water Act. The enforceable regulation for asbestos became effective in 1992, with the maximum contaminant level (MCL) set at 7 million fibres per litre (MFL). Material readily available in the EPA archive states that beyond that level steps, “such as providing alternative drinking water supplies, may be required to prevent serious risks to public health.” The EPA information says the ingestion of asbestos can “cause lung disease; cancer.” The EPA maintains the level 7 MFL was established to “protect against cancer.” Another page on the EPA website cautions: “Some people who drink water containing asbestos well in excess of the maximum contaminant level (MCL) for many years may have an increased risk of developing benign intestinal polyps.”

The National Research Council Canada (NRC), a branch of the federal government, has conducted numerous studies into asbestos cement water pipes. All the NRC studies refer to asbestos fibres in water as a “health concern.” One NRC reports goes even further; “Severely deteriorated AC pipes also released asbestos fibre into the drinking water, and could pose a hazard of tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, and other organs in consumers.” The 2010 study goes on to say “These AC pipes were laid down before the potential environmental, social, and health impacts were recognized and evaluated. In recent years, problems with AC have gradually become significant including increases in the number of pipe breaks and failures.” Yet another NRC report from 2010 points to the potential danger of using showers and humidifiers in homes where asbestos may be in the water.

The World Health Organization (WHO) 2017 fourth edition Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality states: “Asbestos is a known human carcinogen by the inhalation route. Although it has been well studied, there is little convincing evidence of the carcinogenicity of ingested asbestos.”

Health Canada uses the same language, but has added the word “consistent” in front of the word “convincing”, concluding that “There is, therefore, no need to establish a maximum acceptable concentration (MAC) for asbestos in drinking water.”

There are dozens of municipalities across Canada that still use asbestos cement water pipes, servicing homes, businesses and schools.

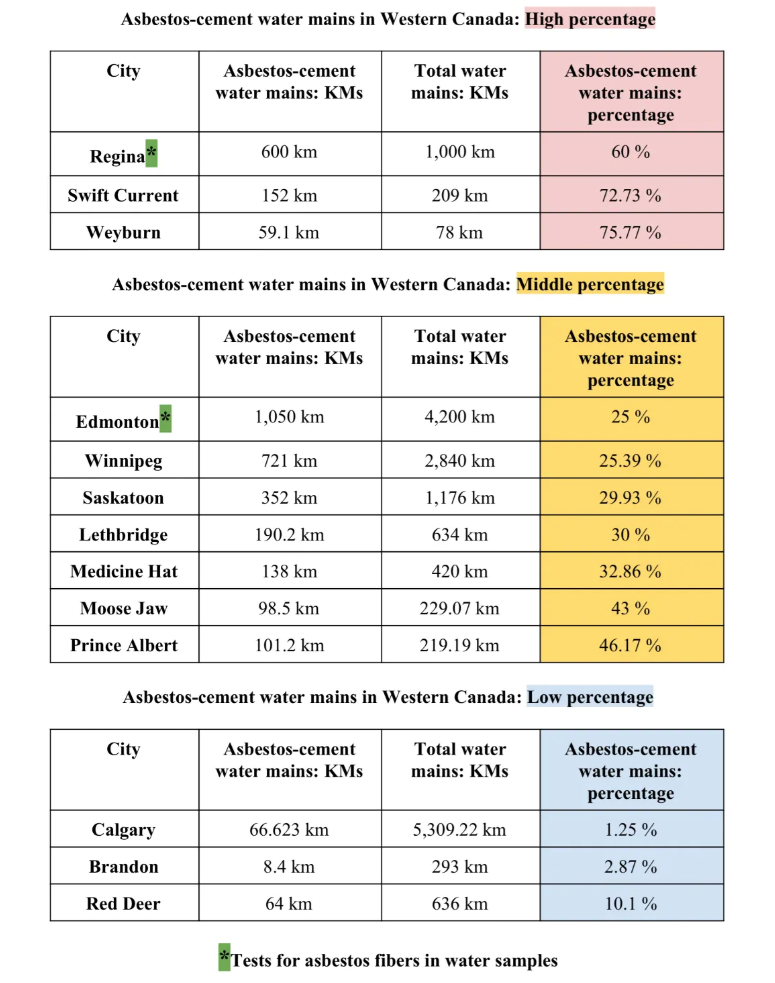

Regina, Saskatchewan has 600 kilometres of asbestos cement water pipes. “These pipes are experiencing more and more failures in recent years and account for almost all of the water main breaks in the city,” reads an NRC report on the matter. The report goes on to refer to asbestos fibres in water as a “health concern.”

In 2012, the former executive director of the municipal branch at the Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment, assured people the water was safe to drink. However, Sam Ferris told the media “There has been some talk about a study coming out the United States that has looked at a linkage between asbestos in drinking water and some benign forms of cancer of the stomach.” Mr. Ferris went on tell journalists that he had not had the time to really look into the report.

Dr. Arthur Frank, a medical doctor and expert in environmental and occupational health, says not regulating asbestos in water is a mistake. “Regulating asbestos in water means that the lives of some Canadians would be saved by not ingesting asbestos in the water they drink, and use in showers,” said Frank, who is based out of Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“There is no question that the ingestion of asbestos, like breathing it, much of which when cleared from the lungs is then ingested, can lead to the development of a variety of cancers, including stomach, small and large intestine, and kidney cancer.”

A 2005 study in Norway looked at the risk of gastrointestinal cancer by 726 lighthouse keepers who had been exposed to asbestos fibres in water. The results state: “Risk of stomach cancer was elevated in the whole cohort.” The Conclusion states: “The results support the hypothesis of an association between ingested asbestos and gastrointestinal cancer risk in general and stomach cancer risk specifically.”

In 2016, Italy released the study Possible health risks from asbestos in drinking water. “Furthermore, the exposure to asbestos by ingestion could explain the epidemiological finding of mesothelioma in subjects certainly unexposed by inhalation,” wrote Agostino Di Ciaula, “In conclusion, several findings suggest that health risks from asbestos could not exclusively derive from inhalation of fibres.”

That report was followed in 2017 by Asbestos ingestion and gastrointestinal cancer: a possible underestimated hazard. The report, which was also authored by Di Ciaula, states, under the subheading Expert commentary; “A risk threshold (AF concentration in drinking water) for digestive cancers has not been convincingly identified so far and regulations, where adopted, have weak scientific basis and may not be adequate. With further and more definitive studies, evidence might become sufficient to justify monitoring plans, persuade countries with no current limits to set a maximum level of AFs in drinking water and might induce a revision of the existing legislations, pointing to efficient primary prevention policies.”

In the years leading up to the asbestos ban, the federal Canadian government promised to “ban asbestos and asbestos-containing products by 2018.” However, a stakeholder from the cement pipe industry lobbied the federal Liberal government. As a result, the regulations do not apply to products containing asbestos already in use before the regulations came into force. Aging AC pipes in the ground under Canadian towns and cities were exempt. On October 18, 2018 Environment Minister Catherine McKenna said “None of these exemptions will impact on human health – that is our top priority.”

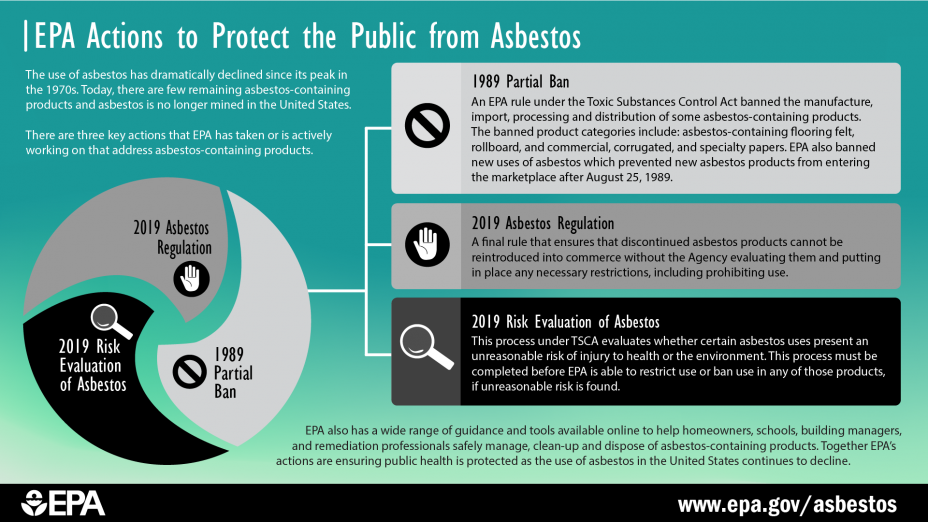

Infographic on Actions to Protect the Public from Asbestos.

Resources:

American Cancer Society. September 15, 2015. Asbestos and Cancer Risk. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/cancer-causes/chemicals/asbestos.html

Asbestos.com and The Mesothelioma Center. June 19, 2023. Asbestos in the Water Supply. https://www.asbestos.com/exposure/water-supply/

Department of the Environment and Department of Health. January 6, 2018. Prohibition of Asbestos and Asbestos Products Regulations. http://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2018/2018-01-06/html/reg3-eng.html

Di Ciaula, A. & Gennaro, V. December 2016. [Possible health risks from asbestos in drinking water.] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27919155/

Government of Canada. December 15, 2016. Government of Canada to ban asbestos (News Release). https://www.canada.ca/en/innovation-science-economic-development/news/2016/12/government-canada-asbestos.html

Health Canada. September 12, 2008. Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality: Guideline Technical Document - Asbestos. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/guidelines-canadian-drinking-water-quality-guideline-technical-document-asbestos.html

Kjaerheim, K., Ulvestad, B., Martinsen, J., & Andersen, A. June 2005. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract and exposure to asbestos in drinking water among lighthouse keepers (Norway). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15986115/

Mnisi, N. Helen Suzman Foundation. January 15, 2020. Asbestos Cement Waterpipes: A Health Hazard? https://hsf.org.za/publications/hsf-briefs/asbestos-cement-waterpipes-a-health-hazard

Radford, E. Regina Leader-Post. October 3, 2020. Testing the waters: Do Regina’s asbestos-cement water mains pose a risk? https://leaderpost.com/news/saskatchewan/there-is-a-risk-western-canadian-cities-do-little-about-their-asbestos-cement-water-mains

Thompson, E. CBC News. October 18, 2018. New federal asbestos ban includes controversial exemptions. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/trudeau-asbestos-cancer-regulations-1.4867684

United States Environmental Protection Agency. 1993. Asbestos: Fact Sheet on a Drinking Water Chemical Contaminant. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/910238YC.PDF?Dockey=910238YC.PDF

Wang, D. L. & Cullimore, D. R. National Research Council Canada. August 1, 2010. Bacteriological challenges to asbestos cement water distribution pipelines. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/accepted/?id=490173b5-8ba7-4559-8a1e-7e08403e1c9d

Wang, D. L., Cullimore, R., Hu, Y., & Chowdhury, R. National Research Council Canada. November 1, 2011. Biodeterioration of asbestos cement (AC) pipe in drinking water distribution systems. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/accepted/?id=084f0596-f366-44d0-b75f-028fc56a71a0

World Health Organization. April 24, 2017. Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edition, incorporating the 1st addendum. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549950